Your cart is currently empty!

Tag: back pain

-

Beyond Chronic Pain: a Personal Journey to Create Healthier Habits

Finding Vitality and Joy in your life

Physiotherapist Jodie Krantz shares her healing journey towards a more satisfying and comfortable way of living within with her own body. Retracing her steps, Jodie invites you to join her on a challenge to improve your own quality of life and perhaps that of your nearest and dearest.

I reached the age of 50 with my body in a condition better than many my age. Being a Physiotherapist I had always done some form of exercise. My weight was in the upper end of the healthy range for my height. I didn’t smoke or drink to excess – ever. I’d always watched what I ate and ‘listened to my stomach’, stopping when I felt full. I considered myself very fortunate to have completed my training as a Feldenkrais practitioner in 1999. This was a profound learning process which gave me access to the tools to keep my body moving like a much younger person, even into old age.

Yet the small aches and pains had accumulated over the years to the point where there was never a day without some sort of pain. Headaches were frequent and although not severe, made me nauseous, fatigued and thick-headed. This very unpleasant feeling would last 2 to 3 days or more. Foot pain made it hard to walk for more then 20 minutes. My lower back twinged frequently, especially after sitting and in bed at night. I often complained to my partner about being tired. Worst of all, severe episodes of lower back pain had seen me bed-bound and off work for up to 5 weeks.

I knew what I had to do, but it was hard to do it. I had to change some fundamental habits I had formed in over 50 years. The intentions I set for myself were:

- To allow myself the ‘luxury’ of getting treatment when needed

- Improve my diet and rid myself of ‘addictions’ – sugar, coffee and alcohol

- Shed a few kilos

- Reduce my stress levels

- Increase my cardio-vascular exercise

- Get enough sleep on a consistent basis

There was no point changing everything at once. The body doesn’t like radical change and it’s usually not sustainable. The biggest challenge I faced was finding the extra time required, a challenge I know that many of my friends, family, colleagues and clients share!

Next birthday I turn 57. In the past few years I’ve turned my life and my pain around. Fatigue as I once knew it, is but a distant memory. I simply feel the happiest I’ve ever been in my life.

-

Flexible Chest and Spine

A Flexible Chest and Spine – The Hidden Key to Freeing the Neck and Back

The Hidden Key to Freeing the Neck, Back and Shoulders

Most people don’t consider their chest and spine as playing a large role in feeling comfortable and at ease through the neck, shoulders and back. The first instinct when dealing with neck and shoulder pain is to spend time working on localised ‘knots’ and muscle tension. However this could be addressing the symptoms, whilst ignoring the underlying cause.

The thoracic spine, and the rib cage serve as the support structure for the entire upper body. Finding comfortable alignment and releasing through the chest and spine allows the rest of the body to relax. In turn, when there is stiffness through the chest and spine, the neck, back and shoulders work overtime to try and correct this, leading to muscle tension, ‘knots’ and pain.

The ‘knots’ are not actually a ball of tangled fibres as you might imagine, they are trigger points. Trigger points are highly sensitive points in the muscles and connective tissue, which can refer pain to other places. In Feldenkrais we don’t massage or manipulate the ‘knots’. Instead we address underlying causes – stress, poor posture and inefficient use of the muscles.

How Feldenkrais Can Help

Feldenkrais uses a process known as ‘sensory-motor learning.’ Students are guided to closely attend to how they are moving, reducing unnecessary and wasted effort. The Feldenkrais Method accesses our brain’s own neuroplasticity, allowing us to revise and replace movement habits which may no longer be serving us.

READ MORE about how Feldenkrais actually works.

BOOK A CLASS or REQUEST AN INDIVIDUAL APPOINTMENT

Our Mental Map of the Thorax

We begin the process of re-educating our posture and muscle use by improving our self-image.

When Moshe Feldenkrais talked about the self-image he was not referring to self-worth or self-concept. What he meant was the sensory map of the entire body that each of us carry in our brain. Our self-image is not totally accurate and is constantly open to change. Neuroplasticity allows us to continually refine and update our mental maps

Our mental map of the thoracic spine and ribs is often particularly vague. For one thing the back of our ribs are out of sight and therefore often out of mind. Secondly, it’s usually the hardest part of the body to reach with the hands. (Think about trying to apply sunscreen in between the shoulder blades!) Thirdly, the sensory nerve endings are spaced far apart in this area compared with say the hands and lips. As a result our ability to feel the difference between 2 different points is poorer in this area.

Improving Awareness of the Chest and Thoracic Spine

The thoracic spine is not only the longest section of the spine, it is also normally the stiffest. The reason for this is the attachment of the ribs cage. The ribs serve the function of protecting the vital organs within the thoracic cavity, including the heart and lungs. Although the ribs are made of bone, they are more flexible than we might imagine. They have moveable joints at the back, where they articulate with the spine. They also have bendable cartilage attachment to the sternum (breast bone) at the front. The lowest 2 ribs are even more flexible, because they don’t attach at the front but ‘float’ freely at one end. For this reason they are called ‘floating ribs’.

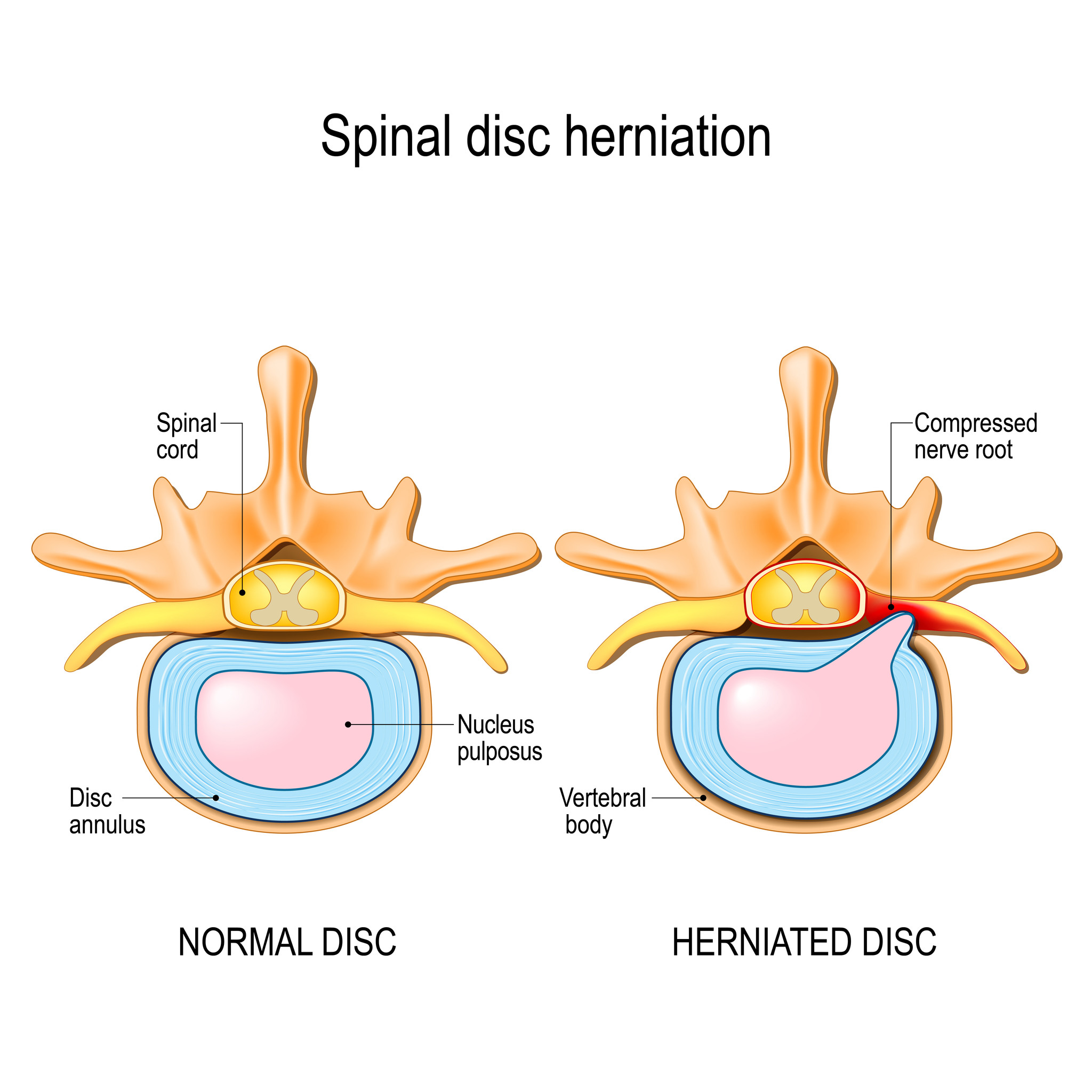

If the thorax is used like an immobile block more strain is shifted onto the relatively mobile neck and lower back vertebrae. Without the protection of the ribs, these sections of the spine are prone to injuries such as cervical or lumbar disc herniations. Learning to better mobilise the chest also helps with the co-ordination of the arms and legs for walking, running and sports and a huge variety of other activities.

The Chest, Ribs and Diaphragm in Breathing

Holding on to unnecessary tension in the chest and abdomen increases the effort required to breath. At times tension is so great that the breath is held completely. At other times breath is not held but it is restricted. This can occur at the end of the breath in or the breath out or somewhere in between. Sacrificing breath markedly impairs our ability to function efficiently and drains energy.

Breath holding and tension around the chest and diaphragm are a common response to physical, mental or emotional stress. Under stress the sympathetic nervous system takes over, resulting in the ‘Fight, Flight or Freeze’ reaction. In our current world we are constantly called upon to achieve, produce results and keep up with a myriad of small and large tasks. This includes keeping up communications through social media and the internet.

Many people use television or social media platforms to relax when they finish work, however the content often keeps the mind revving in high gear. We are losing the art of unwinding and allowing our parasympathetic nervous system take over. The parasympathetic nervous system allows us to ‘rest, digest and repair’. For better sleep and more daytime energy, we need to know how to wind down before we go to bed.

A Mobile Mind and a Comfortable Body

By improving the accuracy of our mental maps as well as the mobility of the chest and ribs we can enhance all of the above functions. We reduce strain on the neck, shoulders and lower back by sharing the work load more evenly. We enhance our ability to easily and comfortably bend and twist the spine in all directions by listening to which sections of the spine are overworking and which could participate more fully. We can connect our limbs to our central axis so that we may use large muscles to provide the power, while smaller ones are reserved for accuracy

Breathing can become simpler, lighter and more spacious, as we learn to use more of ourselves. The mind naturally becomes calmer and our sleep deeper and more refreshing. As we re-discover the pleasure of letting go of excessive effort, our parasympathetic nervous system naturally takes over. Some people even fall asleep during Feldenkrais class – and this is perfectly ok (but we’ll wake you up if you start to snore loudly!)